A bit of a long ramble here as I end the year much learned and probably just as confused, if not more, on what are our intentions, objectives, directions, etc. Looking forward to a good rest and a better 2021.

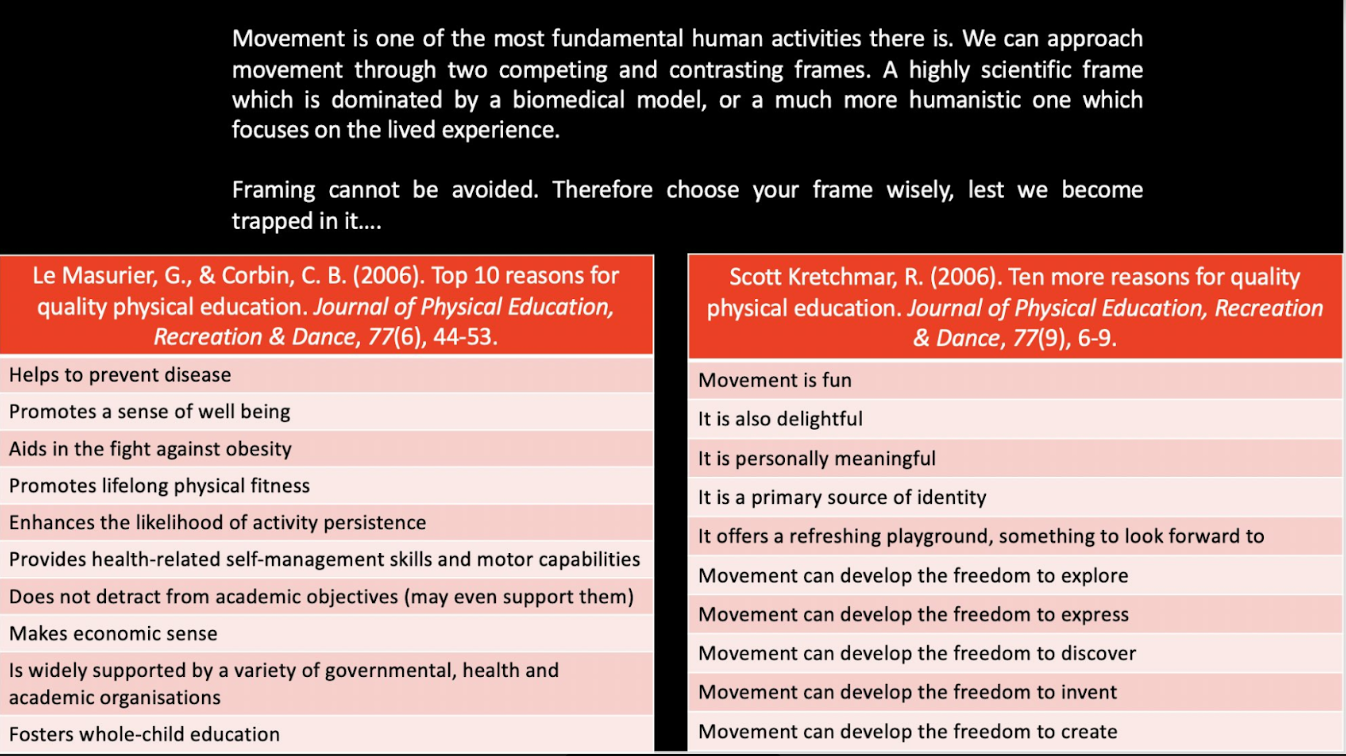

As usual, I try spent time skimming through the world of skill acquisition as best as I can via social media. It is not easy to strike up a face-to-face conversation in this area if you try to do it outside of formal professional development time where even then, it needs strong encouragement to get conversations going. The big assumption I made here (not the best assumption for a holistic picture of PE but adequate for what I want to share here) is that skill acquisition is a big part of our job as PE teachers and it is necessary for us to think about it in order to do better. For us, skills also mean dealing with life competencies, character development, etc. I believe it is important for us to be aware to some extent our role as teachers in general and teachers of skill. The education climate needs to ensure student personal development and sometimes it is easy to take sole responsibility for this in subjects where outcomes are also life affecting, i.e. PE. It is a challenge to see this in perspective. More so in professional development attempts at working towards being a better teacher. Do we spent time on the science and art of skill acquisition (which is broad and also includes affective influencers) or focus more on exploring affective education implementation. Shall we focus on these two broad areas separately? This is an issue that has been debated for long time, died down and sometimes appearing again as objectives of PE become loosely unraveled. When this happens, instant activities are desired for its affective outcome, i.e. giving fun. Being active is relegated as a proxy to healthy living. It seems like stopgap measures. Times like this, we provide PE that is activity focused, as we work towards learners’ immediate well-being, having fun, getting a break, etc. I won’t be surprised that many education scheduling of programmes in this disruptive COVID times include PE for this specific purpose.

As we head towards the end of the academic year from where I am from, we have an awkward two weeks period where PE resumes before school closes for the holiday. There is some concern on my part as to how we approach this and reflecting my insecurities about how we delivering PE. The main questions for me are;

- Is it possible to work towards an explicit education aim and an implicit immediate aim to send students off on a play high at the end of an academic year (or module, term, etc.)?

- Why is there a tension in needing to choose between these hypothetical extremes when there is the claim that explicit skill acquisition via understanding will build up that fun in learning naturally? Our students differentiate very explicitly play and learning. Why? Where did we go wrong?

- Is this tension between the expectations of instant gratification of play that gets in the way of the longer runway of deliberate learning a good tension or are we barking up the wrong tree totally?

I believe a possible missing link to the above questions is the lack of realisation that sometimes we are forcing direct input-output expectations (I want A from introducing B) with learning processes (In order to achieve B, I need to consider process C which requires specific inputs) and there is a mismatch in expectations. I do believe is possible to have both but it requires a balancing act.

My header suggest a fixation of the perfect condition, or rather a hint to the frustrations of models, theories and everything else laying down their claims that seems difficult to fit in to practise. That is exactly what that got me re-looking at my own issues with the field. Inevitably, I spent a lot of time looking into the mechanics of delivering successful skill acquisition experiences. Much of these involve the sciences of the body in context. I am inspired to go further and try to understand the role of movement within our world. This requires some acknowledgement of the importance of philosophy of existence, i.e. how and why do we behave for survival and recreation. It is a lot to think about in wanting to teach in schools but not surprising when at times we are also expected to take care of the affective.

In a recent PE conference I attended, there was a panel discussion session with successful individuals in the area of coaching, sports administration and academia. As much as I listen and take in to their thoughts of movement provision and education, I also wonder what it will be like to deliberately also listen to failures of our attempts to provide good PE in schools. This will allow us to know better the problems that we want to fix. Then almost immediately I realised that our efforts in fixing generalised problems of others (or even emulating successes of others) results is our own generalisation biasedness. It becomes a potentially flawed inductive process of generalising from specific outcomes, especially when there is not a strong physical literacy consensus.

While at policy and broad decision-making level, it is normal to suss out issues and solutions by first identifying problems of others or common ones, this process at the student-teacher level might result in non-learner centred expectations. Learners do not want to know what they do not know. Therefore, any attempts to force a non-learner problem realisation on them is unidirectional. The concept of decomposing a skill seems to be to about providing a solution for the learner based on a problem they have not experienced. These activities may be decontextualized but are solutions to problems that are yet to be experienced by the learner. There are contemporary approaches that attempts to put some responsibility on the individual learner to create learning by generating an action to overcome an immediate scenario where realisation of what is happening is as important as the next step to overcoming it.

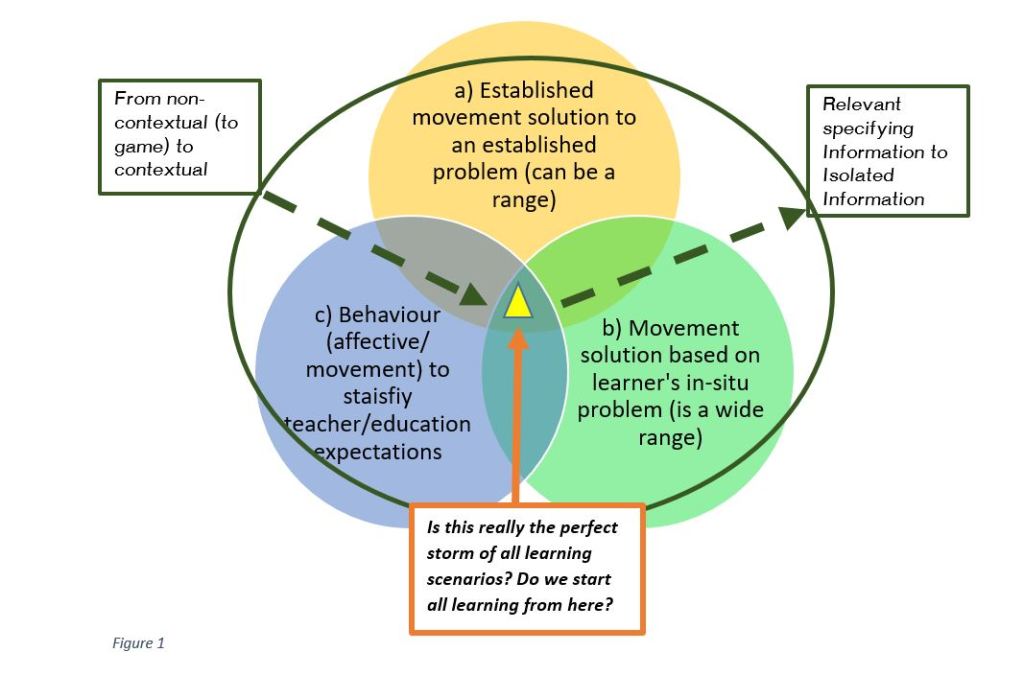

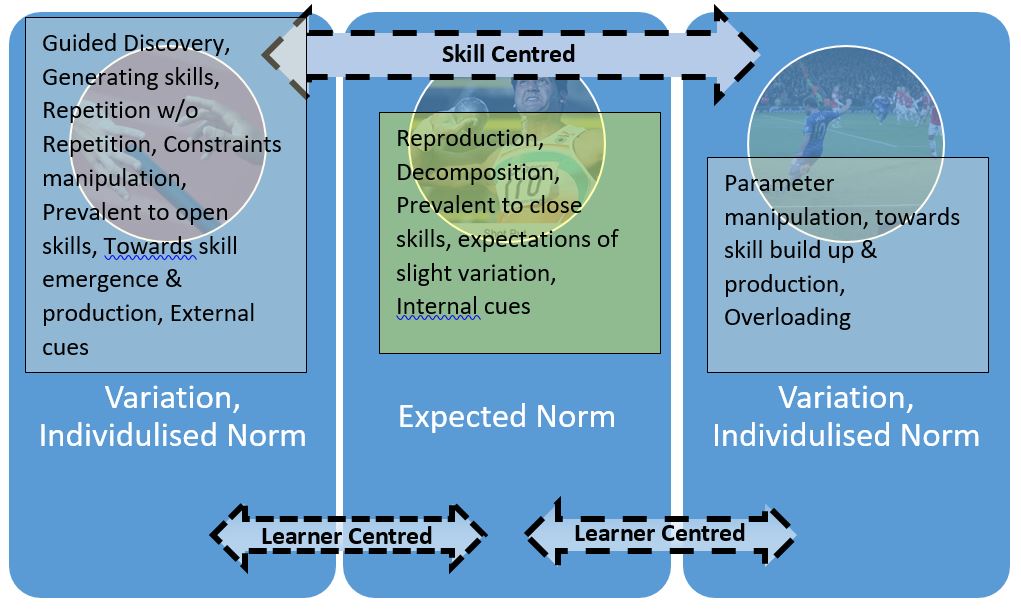

Figure 1

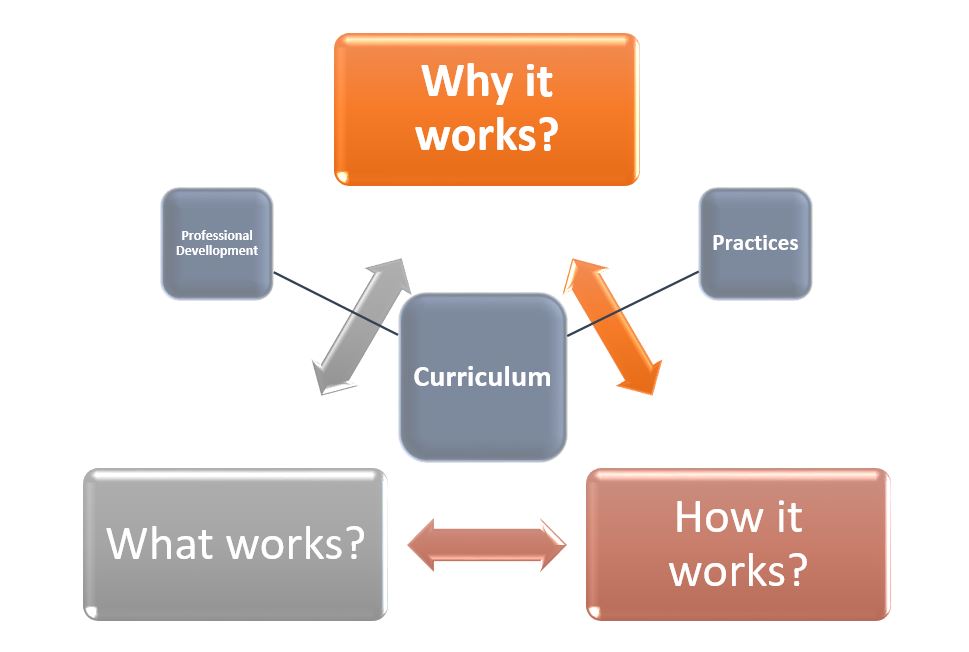

While listening to the presenters and coming away with loads of information, I am very aware that my background understanding of my profession was probably giving me very different perspective than someone else that differs from my views. This contributes to inconsistency amongst us. A big reason for it are the different views of our expectations. The questions put in by attendees were mainly questions that begin with the word “How”. This most of the time points to a problem already identified by a listener or presented by the speaker and the need to find a solution for it. In a particular presentation that included an example of a video of a teacher using a learner centred strategy, one concern that was shared was the lack of proper technique shown. This concern on correct technique may point to a very specific concern in learning which differs from that of the presenter.

A popular view for learning is mechanical linearity, starting from the deconstructed parts and building it up to the whole. For example, technique shapes behaviour and not the other way. It is a challenge to accept that it is possible to be holistic without focusing on the specifics first. If so, we need to accept that not all successful techniques will end up looking exact when they are equally effective in achieving outcome. There is room for both approaches when considering the below.

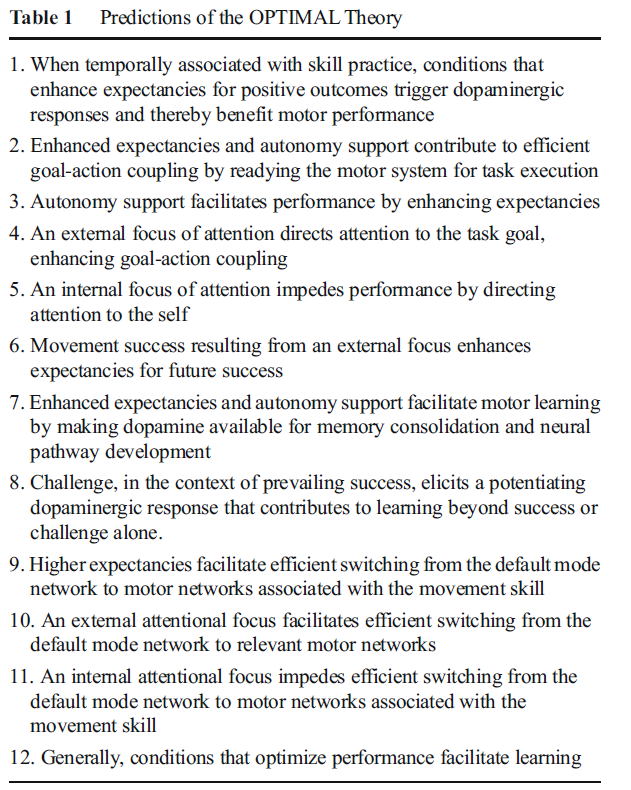

Linearity in learning discussion seems to focus very much on movement and not so much on the motivation to do it that may not be clearly connected to task and environment. This brings to mind the learner’s emotional state what may contribute to this. Optimal Theory of Motor Learning (Wulf), Optimizing Performance Through Intrinsic Motivation and Attention for Learning, brings in this aspect. Cognitive Evaluation Theory, (Deci), looks into motivation in a comprehensive way when considering actions.

One area of influence that is suggested above is the learner’s need to actualise the teacher’s expectations (see Fig 1). Chances are, when the teacher’s expectations are aligned to neurobiological and affective processes for learning at a particular point of learning, we can expect progress that is more efficient. The centre of Fig 1 suggest a scenario where learner’s in-situ movement problem meets the needs of the expected established movement solution and the teachers creating an environment that supports that solution.

If you look at the Venn diagram in Fig 1, I believe a teaching situation can be effectively initiated at different points on the diagram, reflecting different outcomes to teaching. The goal for some may be working from a mental representational model of cognition, i.e. creating different slices of experience to put together eventually, shifting eventually to the centre perfect storm area. The embodied cognition approach, i.e. authentic actions are about needing to accomplish a need of the moment in a representational (note difference in the use of the idea of representation in the mind and in physical lesson) design, usually begins from conditions represented by the centre of the diagram. Circle (b) represents what I think as very underrated, the learner overcoming the problem at hand. This may not be the textbook solution but a learner dependent adaptation.

There is an article by Raab and Araújo (Raab & Araújo, 2019) to get a background of embodied cognition with and without mental representation and their role in learning (different from discussions that pits embodied cognition vs stand-alone cognition). Embodied cognition assumes that cognition is built into action, as opposed to it being mainly stand alone. The great debate here is how information is arrived at for learning and how knowledge of past learning exist and effects this. It is a rather technical paper and the abstract, introduction and conclusion does well to give a reasonable brief if the whole paper prove too much (I struggle trying to figure out very good intentions written in academic style at times).

The theories behind the perspectives of using mental representation outside of embodied cognition are also vigorously debated and one view originates from how we believe our thoughts process works, direct vs indirect perception, and are seemingly at odds with each other. There is some discussion at the academic level to suggest that it is not possible to do well by combining the two school of thoughts. My take is that there is a difficulty in comparing perspectives from different aspects of the same area of interest. This alludes to the missing link comment I made above concerning my original reflective questions.

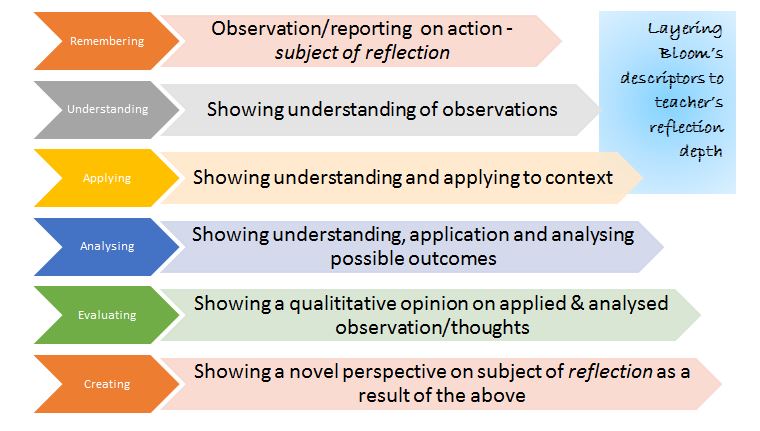

At research level, scientist are focusing on the processes, while teachers/coaches are making decisions based on input and their experiences in dealing with it to achieve intended outcomes. As a teacher, I may be at loss when research evidences of a process that meets my intended outcomes does not meet the input specifications of learners I have to work with in my unique environment (Professional Judgementand Decision Making – PJDM gives some perspective to this). The extrapolations of very good theories for practise are just not getting enough practical attention. This is where we teachers need to be more explicit to complement research.

What do I mean by specifications of my learners in my unique context? Movement solutions are sometimes not all that we are after when we consider the other expectations in an education setting that goes beyond (circle (a) in Fig 1).These includes administrative, affective, teacher-student rapport building, etc. This requires teacher-student relationship that relies largely on interaction, including communication. What many can agree with is what we do with the interaction is the key. This require an almost herculean task of balancing communication, interaction and pure skill acquisition needs.

Fig 1 also shows dashed arrows to suggest that there may be two broad teaching directions, i.e. moving outwards from the centre or inwards towards the centre. For the former, assumption is that learning must start from a perfect storm of task, environment and individual combination. The latter assumes the possibility that outcomes can be achieved from mutually exclusive individual abilities, task, environment and affective focus. While it is ok to believe that learning processes follow a general lawful route, it is also important to realise that learning also depends on what is the learning objective and the impact of social and teacher expectation to outcome.

Sometimes not being clear about outcomes tend to cloud confirming established learning processes, e.g. two teachers not clear on outcomes trying to compare learning processes that differ. If I want to be very specific in a seemingly isolated drill, I could also implicitly want learners to be comfortable with a one to one teacher-student interaction to encourage better rapport or discipline or just wanting to create a relationship. The issue for many I believe is our conflating of outcomes, implicit to boot, that may create a mismatch of teaching approach used and it’s expected outcome. For example, I want to improve shot at goal accuracy while actually trying to improve student management issues. We end up accepting a highly controlled environment as an effective skill teaching scenario when it may do with more varied and organic type activities.

It takes much deliberate awareness by the educator, together with experience, to balance these understanding. I think is very difficult and maybe not even practical to have outcomes that area minutely dissected but rather we tend to work on baskets of expectations (combining affective and mechanics), mimicking the complexity of being in any living situation. It may be potentially detrimental to consider outcomes one at a time and on the flipside, just as worrying if we combine everything and not be too aware of this. This may sound like a cope out in needing to have a clear approach for very specific outcomes but my personal view is that it needs to be a broad approach many times.

Are the basics of an expert the same for the beginner, i.e. both having the same objectives? Does the basics of a beginner shift as they become experts? Are we generalising basic drills as similar for everyone?

For example, what works for a beginner in your context? Recently I noticed quite a popular clip of a well-known NBA player doing very specific and basic dribble and shooting drills, presumably for hours. This went viral with advice for beginners to emulate. It is quite common to see this kind of popular guidance for beginners and “Going back to the basics” is an extremely popular mantra. The key here is are the basics for the beginner and for the expert the same or serve a similar purpose? Can the basics of these two groups of expertise be very different, i.e. can it be something in the middle of the diagram in Fig 1 for beginners who need more specifying information to make sense of movement and is it in the outer edges for experts who can afford to spend more time on isolated opportunities? I will not criticise a beginner for emulating a professional in isolated drills and in fact see it as possible motivating. I will think very carefully if my intention is to improve game play.

Teaching approaches are always heading different directions from different starting points. We are always tweaking them. The perfect storm is not always a fix set of conditions but is very organic and changing to the needs of the learner and almost as important, to that of the expectation of the education environment. The key here is as professionals, we consider learner centeredness and guided by science and art of teaching.

Readings

Raab, M., & Araújo, D. (7 August, 2019). Embodied Cognition With and Without Mental Representations: The Case of Embodied Choices in Sports. Frontiers in Psychology. doi:https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01825

Schematic 1 (Otte, Davids, Millar, & Klatt, 2020)

Schematic 1 (Otte, Davids, Millar, & Klatt, 2020) Schematic 2 (Otte, Davids, Millar, & Klatt, 2020)

Schematic 2 (Otte, Davids, Millar, & Klatt, 2020)

Table 2

Table 2